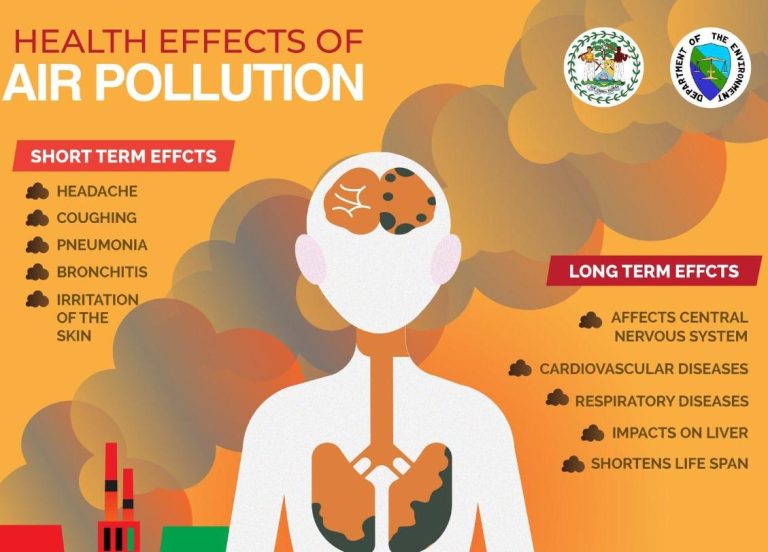

Air pollution, once framed primarily as an environmental concern, is increasingly being identified as a direct and escalating threat to public health. A growing body of research links long- and short-term exposure to fine particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ozone with higher risks of heart and lung disease, strokes, cancers and premature death. Physicians report that vulnerable groups-children, older adults and people in low-income or high-traffic neighborhoods-bear a disproportionate burden, while wildfire smoke and extreme heat are amplifying seasonal spikes in hazardous air.

The mounting evidence is reshaping debates over emissions standards, urban planning and public health preparedness, with implications for hospitals, economies and households worldwide. This article examines what pollutants are driving the risk, who is most affected, and how policymakers and communities are responding as air quality becomes a defining health challenge of the decade.

Table of Contents

- New Research Ties Fine Particulate Pollution to Higher Rates of Heart and Lung Illness

- Children Seniors and Communities of Color Bear the Greatest Burden

- Traffic Congestion Industry and Wildfire Smoke Identified as Leading Sources

- Health Officials Call for Tougher Standards Cleaner Transit and Home Air Filtration

- In Summary

New Research Ties Fine Particulate Pollution to Higher Rates of Heart and Lung Illness

A new peer-reviewed analysis links fine particulate matter – especially PM2.5 – with higher rates of cardiovascular and respiratory illness, drawing on large-scale monitoring data and hospital records. Researchers report that both short-term spikes and long-term exposure are associated with increased emergency visits, hospitalizations, and mortality, with outsized effects in dense urban corridors and communities near major traffic or industrial sources. The findings add to a growing body of evidence that even concentrations below some current standards can carry health risks, sharpening calls for stricter limits and stronger enforcement.

- Cardiovascular impacts: higher incidence of heart attacks, strokes, arrhythmias, and heart failure admissions.

- Respiratory impacts: exacerbations of asthma and COPD, reduced lung function, and more pneumonia cases.

- Disparities: greater burden in lower-income neighborhoods and areas with heavy traffic or industrial activity.

- Exposure pathways: particles small enough to enter the bloodstream, driving systemic inflammation and oxidative stress.

Public-health agencies and clinicians say the results underscore the need for “clean air” interventions that scale from neighborhoods to regions, while offering practical steps for households during high-pollution days. Regulators are weighing tighter standards, expanded monitoring, and accelerated transitions to cleaner energy and transport. Health systems, meanwhile, are preparing for seasonal surges when pollution and heat events overlap.

- Policy levers: stricter emissions limits, targeted enforcement in hot spots, and real-time air-quality alerts.

- Urban design: low-traffic zones, greener streets, and filtration in schools, clinics, and transit hubs.

- Clinical guidance: air-quality-informed care plans for patients with heart and lung disease.

- Personal protection: use of high-efficiency indoor filtration and well-fitted masks during PM2.5 surges.

Children Seniors and Communities of Color Bear the Greatest Burden

Health officials and researchers report that the heaviest impacts fall on those least able to avoid them: children whose lungs are still developing and older adults with preexisting heart and lung disease. Pediatric clinics and emergency departments consistently see more asthma attacks when ozone and fine particle levels rise, and Medicare-based studies show increased hospitalizations and deaths among seniors with even modest day-to-day increases in fine particles. The risks grow during heat waves and wildfire smoke events, when exposure intensifies and indoor air quality also deteriorates. In this context, a small uptick in pollution can translate into disproportionate harm for those at the start and at the end of life.

Public health data further show that neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black, Latino, and Indigenous residents face greater exposure to traffic exhaust, industrial emissions, and port or warehouse corridors-patterns rooted in historic redlining and zoning decisions. Advocates and local officials say these communities endure cumulative burdens: closer proximity to emission sources, fewer trees and cooling infrastructure, and limited access to medical care or home filtration. Researchers have also warned that standard monitor networks may under-detect block-by-block hotspots, masking inequities in exposure and delaying targeted interventions.

- Children: Higher breathing rates and developing airways make them more susceptible to asthma exacerbations during high-ozone and smoke days.

- Older adults: Analyses of large Medicare cohorts link short-term increases in fine particles with elevated risks of heart attacks, strokes, and premature death.

- Communities of color: Studies consistently find higher average exposure to traffic-related pollutants and fine particles, alongside greater asthma prevalence and ER visits.

- Compounding factors: Heat amplifies ozone formation; wildfire smoke penetrates indoors; and housing near busy roadways increases baseline exposure.

Traffic Congestion Industry and Wildfire Smoke Identified as Leading Sources

Health authorities and atmospheric scientists report that urban gridlock, heavy manufacturing, and a surge in smoke events are driving the bulk of recent air-quality alerts, elevating exposure to PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide, and ground-level ozone across major population centers. Monitoring data show that daily peaks now often align with rush-hour traffic and downwind industrial activity, while smoke plumes from regional fires have extended hazardous conditions hundreds of miles beyond burn zones.

- Traffic corridors: Tailpipe gases and ultrafine particles, plus brake and tire wear, concentrate along highways and city streets.

- Industrial hubs: Refineries, metalworks, and chemical plants emit sulfur compounds and VOCs that contribute to secondary pollutants.

- Smoke intrusions: Wildfire plumes laden with soot and fine particulate matter degrade air rapidly, even far from ignition sites.

Clinicians and public health departments cite rising asthma exacerbations, cardiovascular strain, and increased emergency visits, with disproportionate effects in neighborhoods adjacent to busy roads and fence-line facilities. With hotter, drier conditions intensifying burn seasons and ozone formation, researchers say targeted strategies are gaining urgency.

- Traffic demand management: Congestion pricing, expanded transit, and zero-emission truck and bus fleets.

- Industrial controls: Tighter emissions limits, advanced scrubbers, and leak detection/repair for VOC sources.

- Smoke readiness: Rapid alerts, clean-air shelters, and upgraded filtration in homes and schools during smoke days.

Health Officials Call for Tougher Standards Cleaner Transit and Home Air Filtration

Public-health leaders across several jurisdictions signaled a coordinated push to curb exposure to fine particles and traffic-related gases, citing new analyses linking routine pollution spikes to higher cardiopulmonary admissions and lost workdays. Officials said they will press regulators for tighter emissions limits, more aggressive enforcement near freight corridors, and expanded monitoring to capture wildfire smoke intrusions that increasingly drive seasonal surges. They also highlighted disparities, noting that communities bordering highways and warehouses bear a disproportionate burden and require targeted protections.

The emerging policy package centers on cutting pollution at the source while hardening indoor environments where residents spend most of their time. Agencies outlined plans to accelerate zero-emission buses and delivery fleets, update building ventilation guidance for schools and multifamily housing, and provide rebates for high-efficiency filters and portable purifiers. Health departments also want real-time alerts tied to localized sensor networks, along with employer protocols that limit outdoor work when air quality deteriorates. Funding proposals, officials said, will prioritize neighborhoods with the greatest health risk and the least capacity to adapt.

- Stronger standards: Tighter limits for PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide, coupled with enforcement focused on industrial hot spots and freight hubs.

- Cleaner transit: Faster retirement of diesel buses and trucks, anti-idling controls, and incentives for zero-emission last-mile delivery.

- Home air filtration: Rebates for MERV-13 or higher furnace filters, HEPA purifiers for bedrooms and living areas, and updated guidance for safe DIY smoke filtration.

- Data and alerts: Dense, neighborhood-level sensors feeding public dashboards and mobile alerts that trigger school and workplace precautions.

- Equity safeguards: Targeted investments, multilingual outreach, and community-led monitoring to ensure benefits reach those most affected.

In Summary

As evidence linking dirty air to higher rates of disease and premature death continues to mount, public health agencies say the greatest risks fall on children, older adults, and people with preexisting conditions, particularly in neighborhoods nearest major roads and industrial sites. Researchers note that even short-term spikes in pollution can trigger serious health events, underscoring the importance of timely alerts and access to cleaner indoor air.

Regulators in several regions are weighing tougher standards and expanded monitoring, while cities pilot measures to curb traffic emissions and address smoke from increasingly frequent wildfires. How quickly those steps move forward-and how evenly protections are implemented-will shape the health impacts felt this year and beyond. Officials advise residents to track local air-quality indices and follow medical guidance on high-pollution days as policy debates play out.